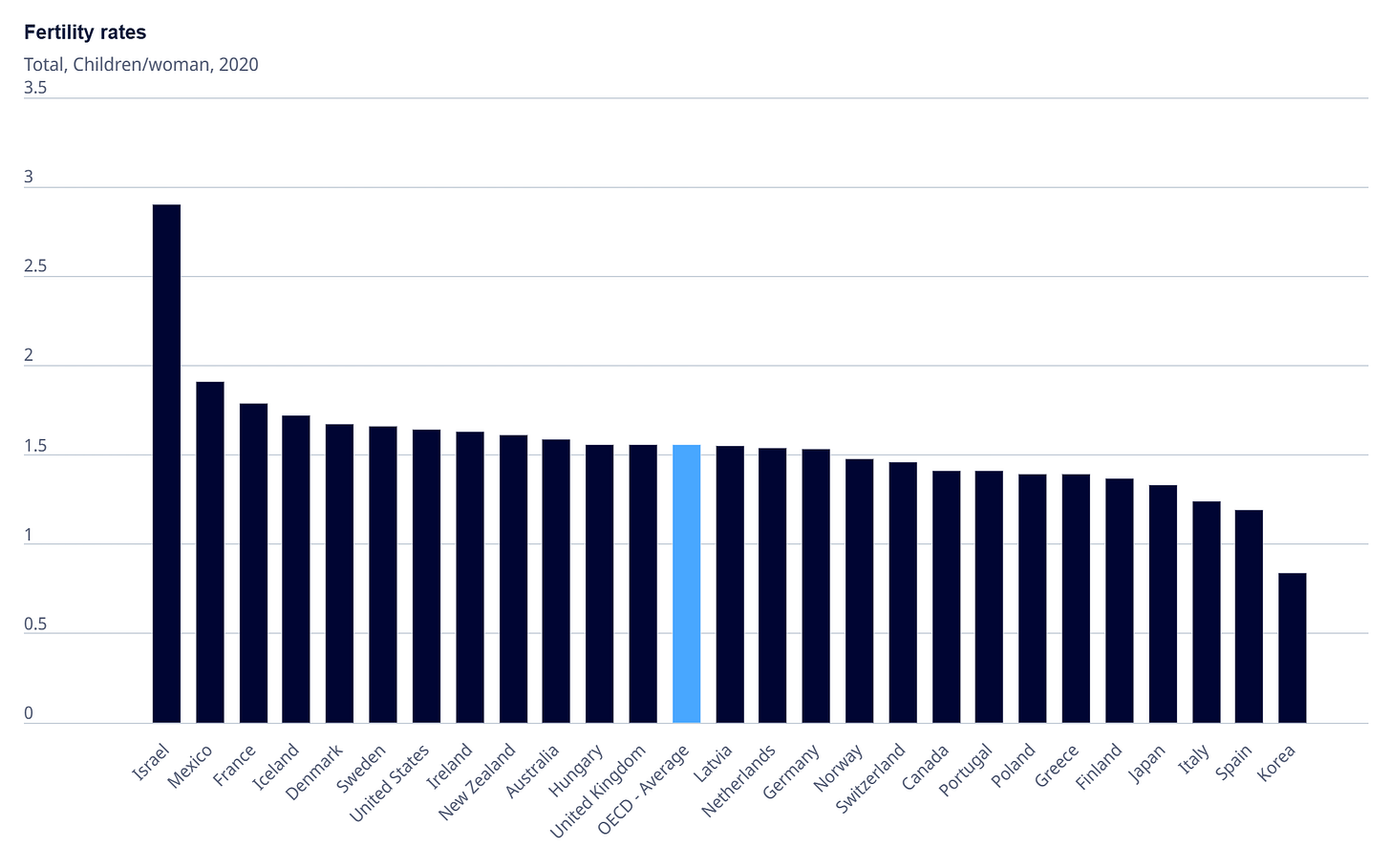

A silent crisis is unfolding across developed nations: fertility rates are collapsing at an unprecedented rate. In 2020, the OECD average total fertility rate was just 1.56 births per woman, well below the 2.1 births per woman needed to keep population stable.1 The problem seemingly has no borders despite the differing cultures and societal norms across countries and the various support programs many governments have enacted in a desperate attempt to deal with the oncoming demographic crisis.

Despite having some of the world's most generous parental leave policies and childcare support, Norway's fertility rate was just 1.48 births per woman in 2020, while Denmark's was 1.68—similar to the United States, despite having far more robust family support programs in place. This leaves governments worldwide grappling with a difficult question: Is it possible to convince people to have more children in a developed economy?

Economic Barriers and Fertility Rates

There are two common opposing viewpoints on this question. The first group suggests that the problem is economic challenges preventing people from having children. Children are expensive and time-consuming. Having a child can mean making economic sacrifices, living below the means to which you have grown accustomed, and potentially sidelining career prospects to prioritize your family. Proponents of this view suggest government policies that ease these restraints on potential parents, such as a child tax credit, subsidized daycare, and paid parental leave.

The argument against this is that many countries have implemented these policies with little to no impact on fertility rates. Hungary's government spends over 5% of its GDP on family support, yet their fertility rate remains at a dismal 1.56 births per woman. This is lower than the United States, at 1.64 births per woman, one of the few countries in the world that does not offer national paid parental leave. These trends suggest that the problem is societal, that views around children have changed, and fertility rates reflect that.

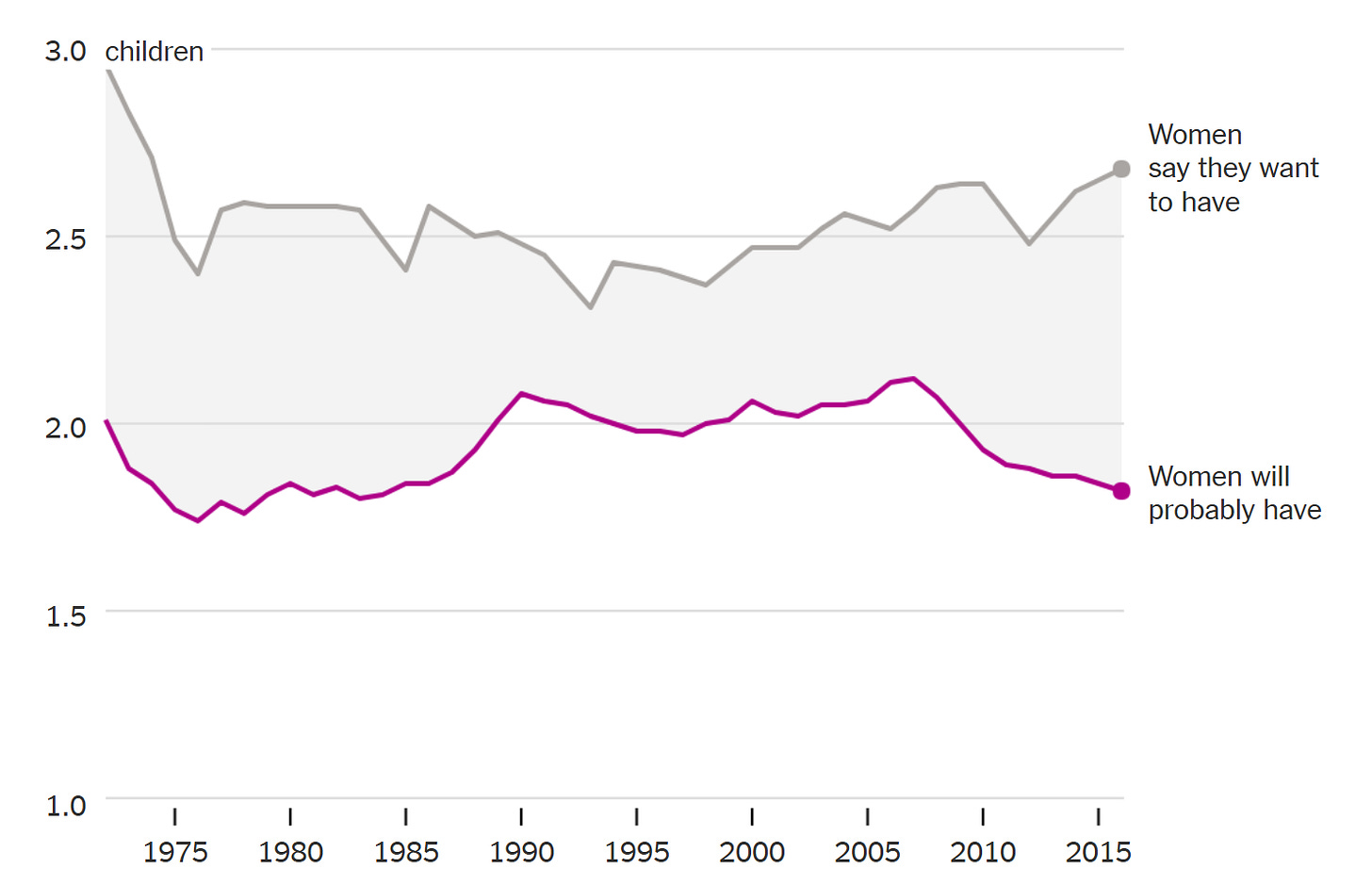

However, this doesn’t capture the full picture either. Data collected from the General Social Survey in 2015 suggests that the average number of children American women want to have is around 2.7, slightly higher than the average of 2.6 in 1980. The desire for children is alive and well, but the disconnect between the number of children desired and the number of children born is staggering. So, what's happening?

Shifting Patterns of Parenthood

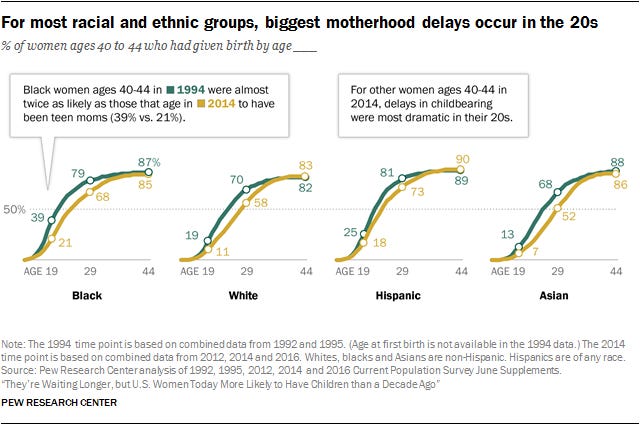

The way people are having children is far different from what was common in much of the 20th century. The policies enacted to encourage planned families through the use of birth control to combat high rates of teenage pregnancy and unplanned pregnancy were very effective. Pew Research reports that in 1994, 22% of women aged 40-44 had become mothers during their teenage years, compared to 13% among the same age group in 2014. This trend is even more pronounced among Black women: 39% of Black women aged 40-44 reported becoming mothers in their teenage years in 1994, down to 21% in 2014. This is a large contributor to the change in fertility rates despite the relatively stagnant change in desired children.

Women used to have more unplanned pregnancies. However, the shift to planned parenthood did not reduce the number of mothers—it changed the age at which they had children. While it's true that women in 2014 were much less likely to have been teen mothers than their counterparts in 1994, by the age of 34, the gap nearly closes. In 1994, 80% of women reported being mothers by the age of 34, and in 2014, 77%. By the age of 44, women in 2014 were slightly more likely to be mothers, at 85%, compared to 83% in 1994.

All of this suggests that the current total fertility statistics may be slightly misleading. While older generations were more likely to have children as teenagers or young adults and less likely to have them in their 30s or 40s, the trend seems to have reversed among millennials and, if the trend continues, with Gen Z as well. Because the total fertility rate is calculated by taking snapshots of the fertility rates of each age group in a given year, it may not correctly account for the fact that young women today may be more likely to have children in their 30s or 40s than the women who are currently in their 30s or 40s. It's unlikely this can entirely explain the unprecedented decrease in total fertility, but it does help frame the issue. The government does not need to convince people to want children; it needs to help them feel prepared to have them.

The Age Problem: Challenges of Delayed Childbearing

The fact that people are having children at older ages presents several problems. Fertility is lower at older ages, making it more difficult to become pregnant, and when a woman does become pregnant, complications are more likely in her 40s and mid-to-late 30s than earlier in life. This difficulty means parents may be more inclined to have fewer children than they originally intended. It also means slower growth for the population. More babies are born if the average age of a mother is 25 compared to 30.

State pension systems and other social programs rely on having a large workforce to draw taxes from in order to fund those who are drawing more than they contribute—namely, seniors. Consider the perspective of a single family: A woman has a child at 25, her child then grows older and has a child of their own at 25, and this process continues. By the time the original woman is 75, three generations would have been born. If the age of childbirth shifts to 30, only two generations would exist by 75, and the third wouldn’t be born until she is 90. This plays out a bit differently on a national scale, but as the average age of a mother increases, the size of the workforce that supports seniors and other groups that benefit from government assistance decreases.

The Complexity of Family Formation

Putting people into a position where they feel comfortable having children at a younger age is a much more complex prospect than pointing to a single economic or social constraint. Consider the goals the average individual may wish to accomplish before having a child: being happily married, owning a home, feeling established and successful within their career, and achieving financial stability. None of these goals can entirely be summed up as purely economic or purely social.

For instance, one might conclude that simply making housing more affordable will result in couples feeling they're able to have children more quickly. In truth, the results are mixed. Even if homes were cheaper today (adjusted for inflation) than in the 1960s, the average home-buying age would likely still be higher. A 20-year-old in the 1960s likely started their career and was considering marriage, giving them more reason to buy a home than a 20-year-old today, who may still be in college and far from getting married. This does not mean housing affordability plays no role, but it does mean it is not the primary factor causing people to wait.

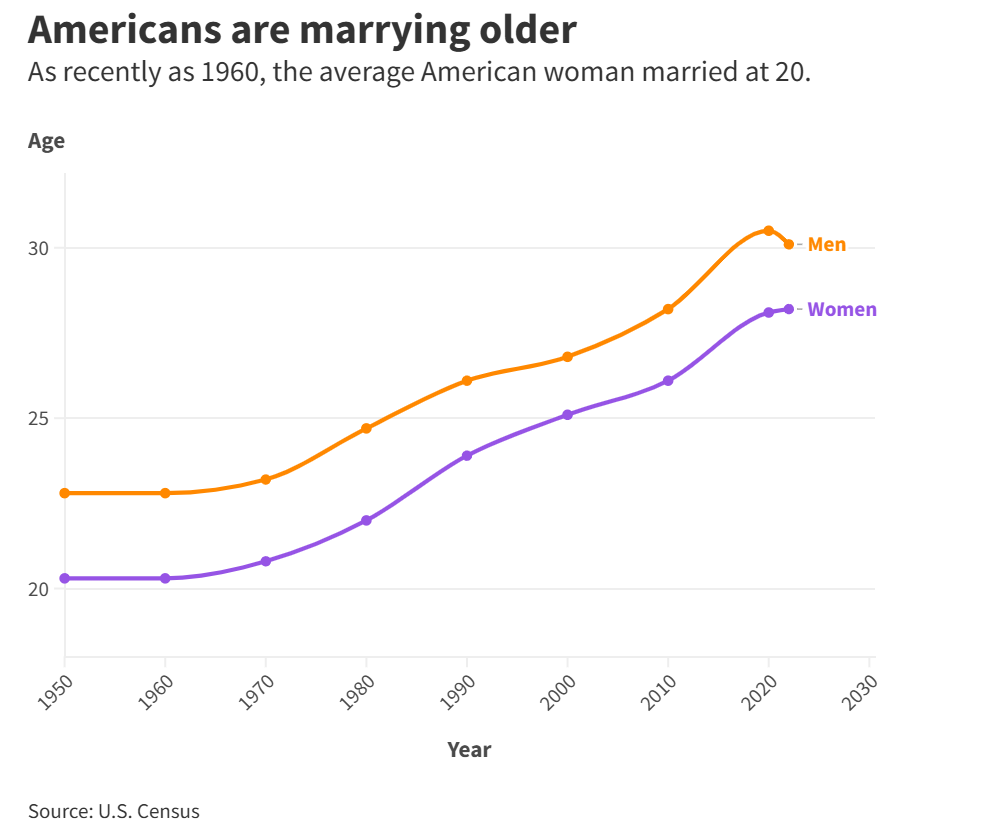

You could also look at marriages and assume the problem is wholly social. People choose to get married later and, as a result, have children later. But why are people today more likely to get married later in life? Several factors contribute, such as the decline in religion among younger generations and the increased prevalence of cohabitation. However, another reason is that there are simply more hurdles to overcome today before marriage is considered.

Education and Career: The Hidden Fertility Barrier

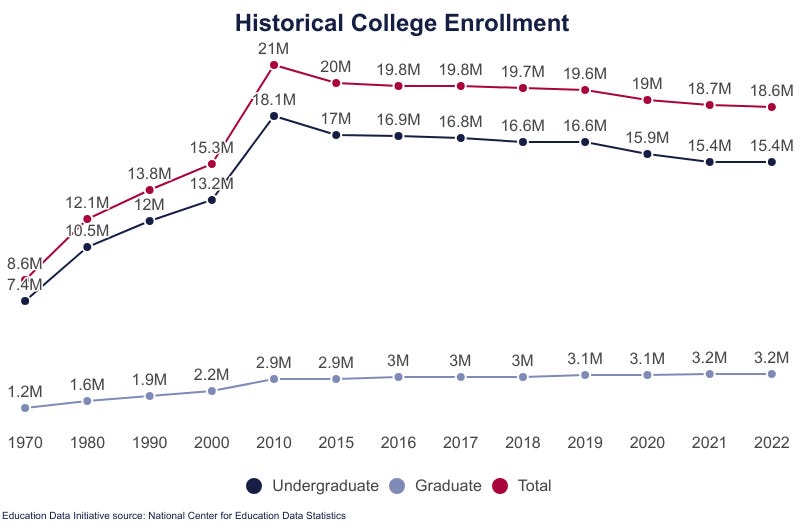

The reason why many government programs fail to influence total fertility rates or lower the average age at which women have children is that they fail to address the core issue. If the demographic crisis is as significant as some claim, far more radical solutions are needed than child tax credits. The largest factor influencing the age at which a woman has a child is education.

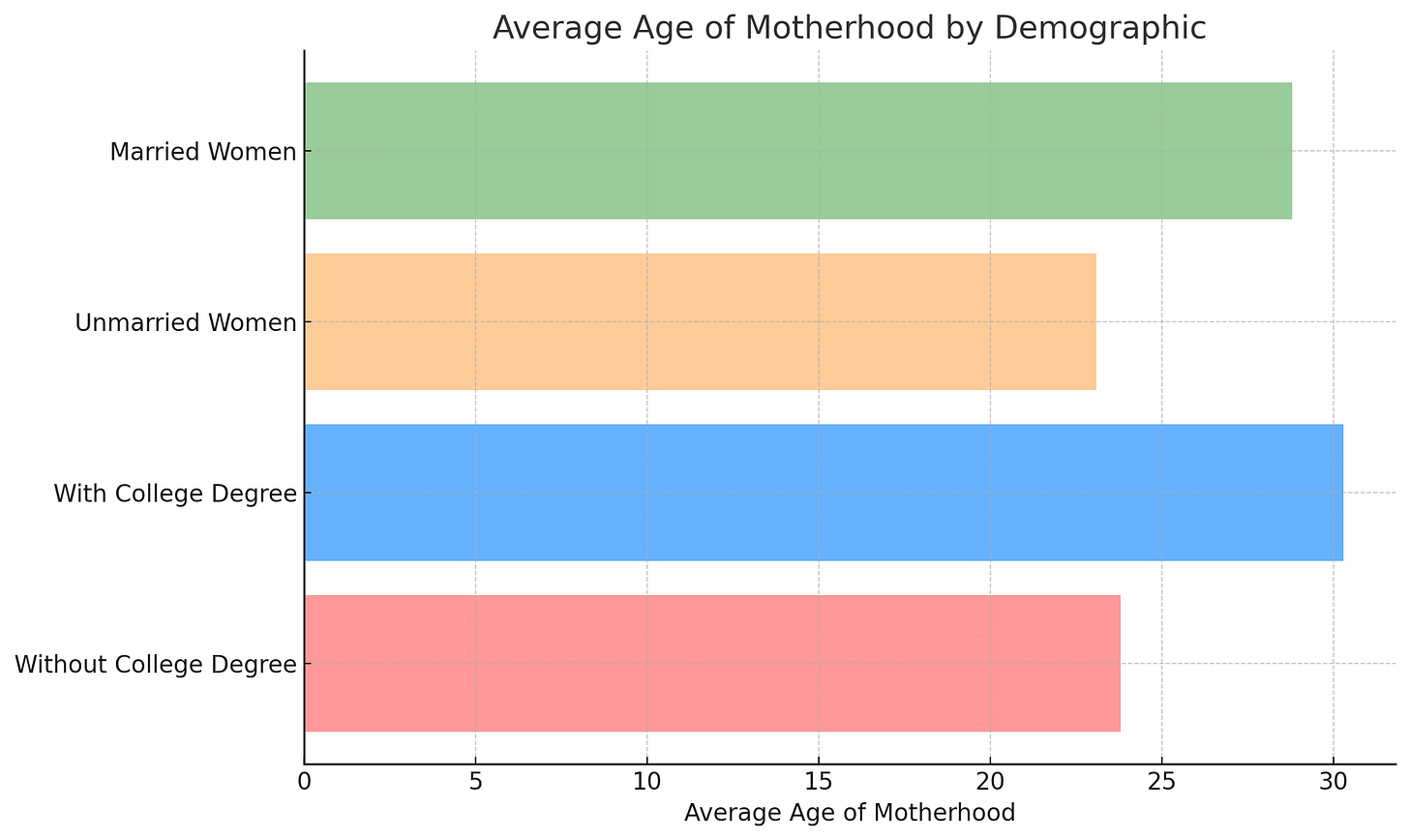

In the United States, the average age for a woman without a college degree to have a child is 23.8 compared to 30.3 for those with a college degree.

The simple explanation is that those without a college degree are more likely to have unplanned pregnancies. However, unplanned pregnancies have decreased across all education levels, even as the age gap has widened. A better explanation may be that someone who has not gone to college is much less likely to define success based on their career.

Career fulfillment and upward mobility are much more important to someone who has invested years and significant resources into their education than to someone who entered a low-skilled job right after high school. Climbing the career ladder takes time, and for many graduates, it will not be until they reach those goals that they will consider starting a family. While child tax credits and subsidized daycare can help with time management and economic concerns, they're ultimately a minor concession if someone feels distant from their career goals.

The solution is to accelerate the period between leaving high school and entering the workforce. Expand options for 3-year accelerated bachelor's degrees, encourage students to pursue trade schools and community colleges when suitable, increase opportunities for paid co-ops, and create more dual-enrollment classes for high school students. The quicker young adults can enter the workforce and work toward their career goals, the quicker they'll be able to consider starting a family.

This is an example of how policy can be oriented toward removing barriers instead of primarily subsidizing children. Many young people perceive a 4-year barrier before they can truly begin their adult lives. Is that barrier necessary in the exact way it currently exists?

Unplanned Pregnancies and Support Systems

While unplanned pregnancies are certainly less common, they still happen on a regular basis. Just as it is in the best interest of the state to convince prospective parents who are not with child that they can support children, it is also in the state's interest to convince prospective parents who are with child. Currently, young women in high school or college who experience an unplanned pregnancy often choose abortion. In 2020, the Guttmacher Institute reported 930,160 abortions across all 50 states and DC.

To raise fertility rates, policies should be pursued that offer alternatives to abortion, giving women more confidence in raising a child. This idea may seem controversial at first; after all, several studies show that around 95% of women do not regret their decision to get an abortion. The problem with that statistic is that it does not explain why women believe their decision was right. For instance, a woman can believe she made the right choice in getting an abortion because she felt there would not be enough support if she were to have the baby.

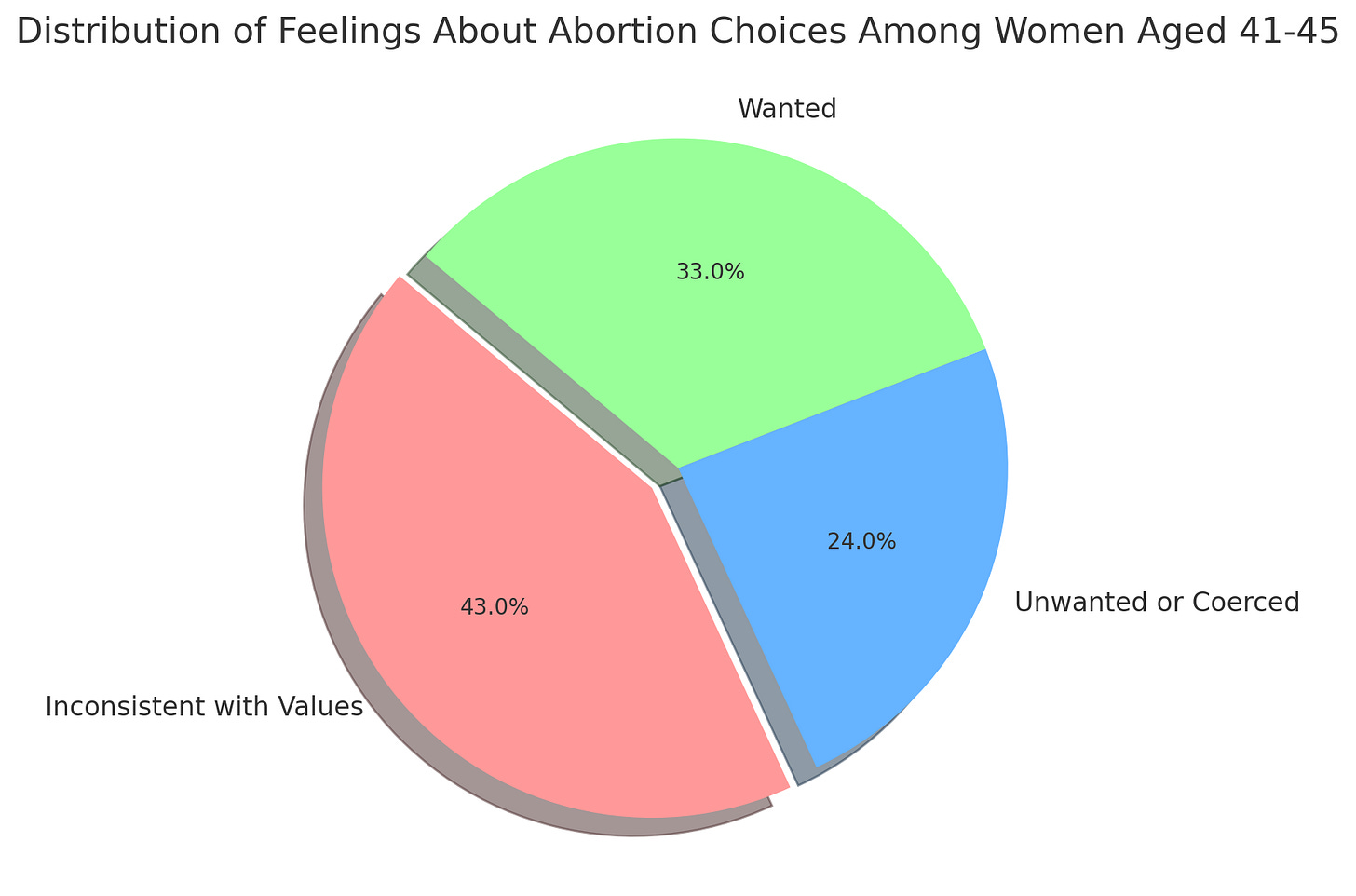

On either side of the political aisle, it should be agreed that a woman should not feel obligated to get an abortion due to a lack of support, financial strain, or being coerced into the decision. A study published in the Cureus Journal of Medical Science on 1,000 American women aged 41-45, 226 of whom reported having a history of abortion, found that 43% accepted their choice but felt it was inconsistent with their values and preferences, 24% reported it as unwanted or coerced, and 33% identified it as wanted. Further, 60% of women reported that they would have carried the baby to term if they had more support and/or financial security.

Options for carrying babies to term need to be as widely available as abortion. Women should have access to advisors who can help them explore available government programs and financial incentives to raise a child. Financial support specifically geared toward single mothers should be created at the national level so that women do not feel reliant on food stamps and assisted living if they carry the baby to term. In this issue, the importance of choice cannot be stressed enough; women need to feel that they truly have a choice between abortion and raising the child—not that the latter will derail their life.

Social and Cultural Dynamics

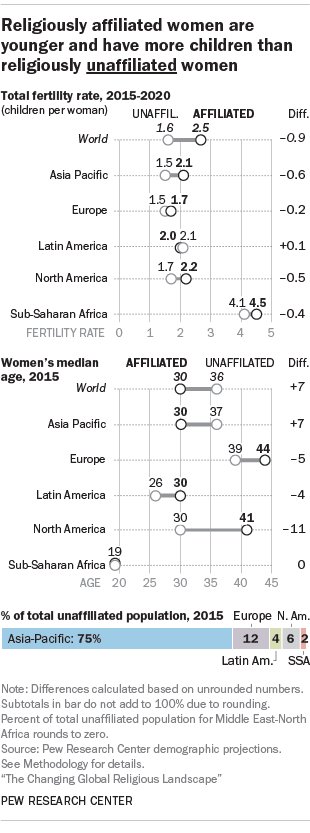

Often when this issue is discussed, the group who believes the problem is entirely economic thinks the state can fix it easily, while the group who believes the problem is entirely social believes the state may not be able to do anything about it. And, of course, social issues do play a very large role. Religious people are more likely to have children than non-religious people. They're also more likely to have them at a younger age. In much of the developed world, society has become less religious.

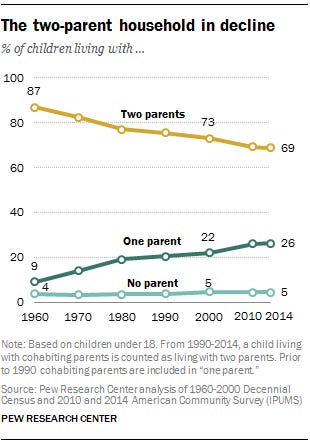

Attitudes around marriage have also changed. Cohabiting before marriage is now common for large portions of the population, and those who cohabit are often likely to wait longer to get married and longer to have children. Historically, if a woman experienced an unplanned pregnancy, there was social pressure for the man to marry her. Now, a large portion of the population does not live in two-parent households. All of this plays a role in how individuals view children and their values.

Despite this, the government does have the ability to make substantial changes to encourage people to have children. While in a liberal democracy, a government should not attempt to make society more or less religious nor define the correct context of marriage, but it can respond to the fact that most people want children, but they are not having them.

Conclusion: Breaking Down Barriers

The decline in fertility requires unconventional solutions, highlighting flaws in society’s structure. The 4-year university system and considering abortion as the standard for unplanned pregnancies are norms we have accepted, but they need to be reconsidered. While child tax credits and subsidized daycare are good policies, efforts need to go beyond that if the trend is to change.

These two focus areas are just the beginning. We need to ask whether children have become stigmatized in public spaces, whether home and community design are no longer ideal for raising families, why fewer young people are dating, and why marriages are increasingly delayed. There are social effects beyond the government's reach, but as long as people continue to desire more children than they are having, governments must shift from merely acknowledging the problem to actively dismantling the barriers that prevent families from thriving.

The only OECD country to buck this trend is Israel, with a total fertility rate well over replacement at 2.9 births per woman. However, this appears to be primarily driven by Israel's unique ethnic and religious makeup rather than specific policy choices.