In 1996, the president of Taiwan was Lǐ Dēnghuī'. He decided to visit the United States, causing China to react by firing missiles into the waters near Taiwan, and mobilizing the Fujan region. The United States sent an aircraft carrier in, and China withdrew the mobilization order, stopped firing missiles, and the waters of the Taiwan strait settled back down to an uneasy peace.

The year is 2025, and this world’s power structure feels very, very different. Xi Jinping has been upping his rhetoric as of late, but it feels pundits have been saying that every year for the last decade.

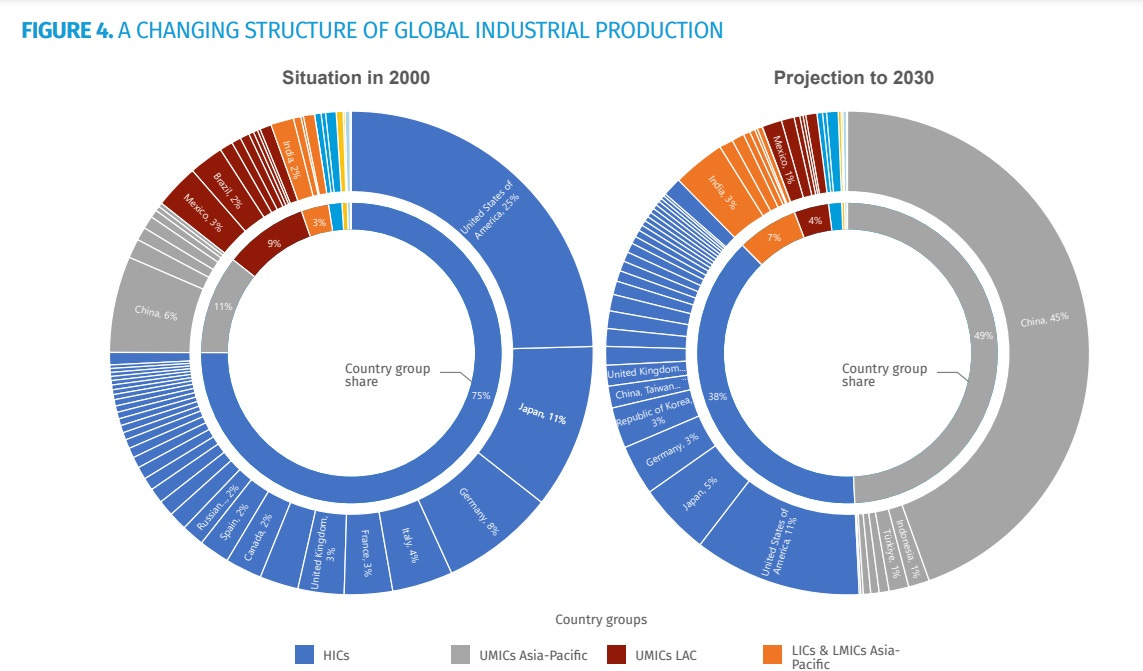

Bringing the self-governed province back in line with mainland China has been a goal of Xi's for a long while. China has been biding its time since 1996, since 1949, really. It has been modernizing its anti-ship, anti-aircraft, and anti-submarine capabilities, and is well on its way to surpass the U.S. Navy in its number of blue water ships. (so much for the two-power standard model) Xi Jinping has also invested heavily in cyber-warfare, and rejigged China’s economy (through industrial policy spending) to gear it towards industries which will be useful come war-time, such as drone manufacturing, battery production, chemicals, autos, aircraft, ships, and semiconductors. This industrial policy spending is comparatively massive, and has had high returns for China’s manufacturing capabilities:

Looking at this graph does not create much hope. The U.S. and its allies have lost a lot of ground to China. Why does this all matter? Ask yourself why and who won World War 2. The United States was able to defeat Japan and Germany at the same time because of its amazing industrial capacity. Lesser so but still true for the Soviet Union. After World War 1, manufacturing ability has been the most important variable in warfare. And the U.S. is losing this front.

However, as of 2025, the U.S. is still fairly competitive in terms of a pure military strategy. In fact, if the objective is a defence of Taiwan, the U.S. is very likely to succeed. This essay isn’t meant to assure you that the (neo?)-allies will win, it is meant to change your probabilities on the matter. I see a lot of dower and pessimistic predictions about the U.S.’s chances, based purely off economic extrapolation. I think much of this is pragmatic, the louder you sound the alarm bells, the more likely the Congress is to realize the danger of the situation. But even still, I disagree with the pessimism. So let me explain why I think the U.S. is very likely to win in the next few years, although as you will see, the probabilities get worse as time goes on, depending on a few key decisions made in D.C., Tokyo, and Taipei.

First, let’s peel these layers back, all the way down to theory. Carl Von Clausewitz famously wrote that “War is nothing but a continuation of politics with the admixture of other means.” In politics, groups compete to impose their will to power over others. In war, states fight to impose their will to power over other states. This is done in pursuit of some goal. To achieve this goal, sufficient military superiority over another state is needed. In World War 2, Hitler wanted to populate western Russia with ‘Aryans’. For this goal, he gave the name Lebensraum. But in order to achieve this goal, he had to evict the Soviet military. Xi Jinping wants to annex Taiwan. Taiwan, like the Soviets, has refused to let that happen voluntarily. Thus, war.

As important as manufacturing is, there are also other, maybe more subtle variables, that I don’t see talked about enough in the discourse. Noah Smith writes a lot about China’s scary manufacturing abilities, and looking at the above graph, one might get the impression that China simply has this war in the bag. This would be a mistake. The United States and the Soviet Union lost in Afghanistan, remind me how immense Afghanistan’s manufacturing capabilities were? The U.S. was unable to defeat China in the Korean war, despite the fact that China was basically still rural and undeveloped. This is not to dismiss economic variables, but to shed light on ones which are underrated. But you’re just changing the subject! The economist says. Don’t worry, after the military strategy section, I’ll make an argument against the econ pessimists as well.

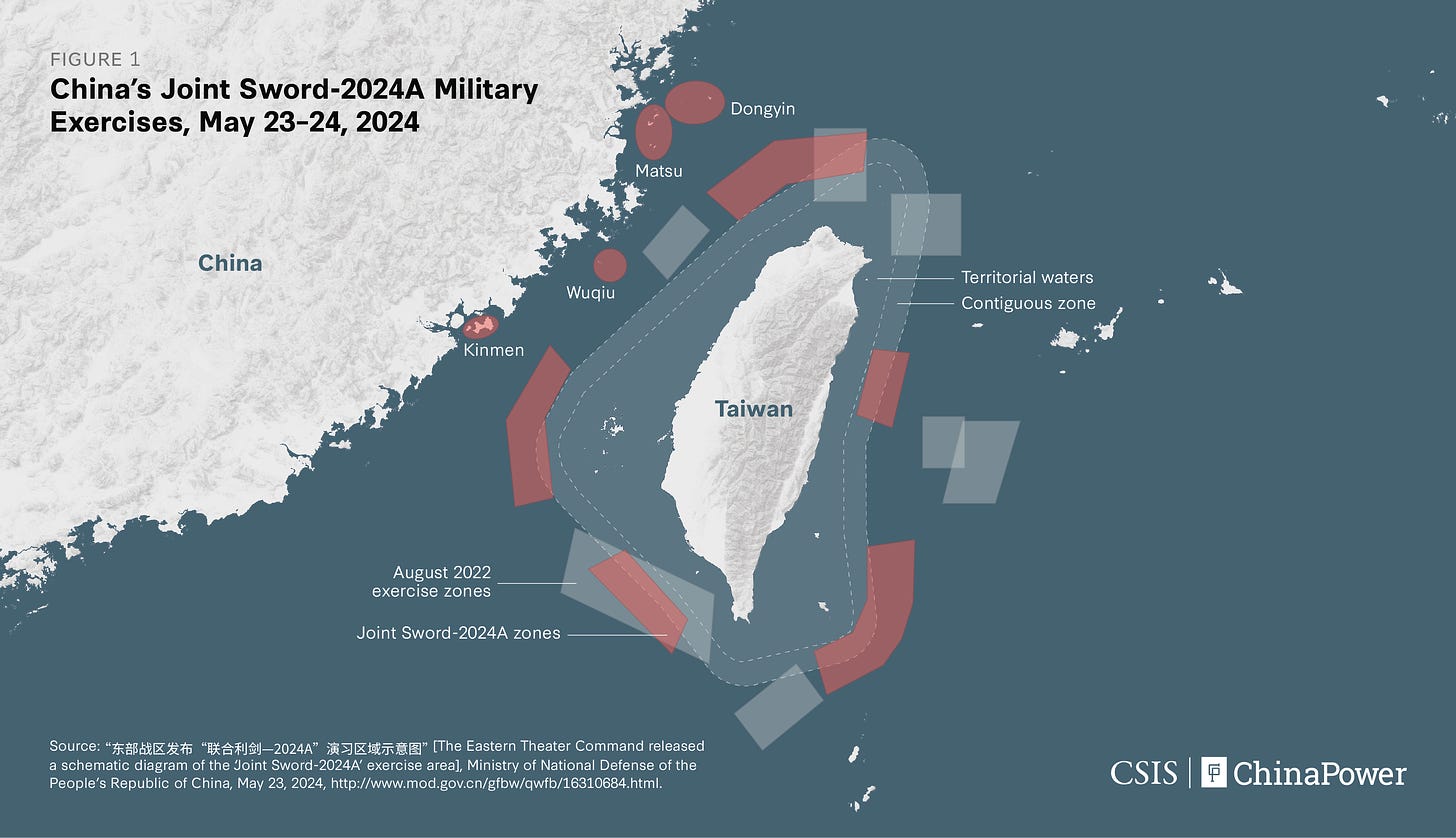

Let’s start with the scenario. China invades Taiwan in 2026. The CSIS, a major think-tank in D.C., ran 24 different versions of the same war game, and a naval blockade was by the far the most likely first step. China has run naval exercises simulating this encirlement multiple times in the past 5 years, which ups the probability.

Now the United States has to respond. The problem is that, although the U.S. will still have more ships then China in 2026, they are spread throughout the world, and only a fraction (The Seventh Fleet) are in the waters of East Asia. China of course has all of it’s ships in the area, so in the short term, China has a larger navy.

In most of CSIS’s wargames, although China received heavy losses to it’s navy, the U.S. was unable to secure either naval or air superiority over the Taiwan strait. This makes sense and is a high probability outcome. This also paves the way for an invasion of the mainland. However, keep in mind that Taiwan is 100 miles away, twice the length of the D-Day invasion distance. This is important because naval invasions are one of the hardest, if not the hardest military maneuver to accomplish in war. The logistics of sending exposed troops across 100 miles of open water under possible aircraft and submarine fire is so difficult that on this scale, it’s only been accomplished once in military history. And that was under the most peaceful of conditions, with full allied control of the English Channel. Needless to say the distance and the less then fully controlled nature of the strait, along with innovations in missile technology since the 1940s, will make this invasion far more dangerous and complex then Operation Overlord. Your probabilities of success should update…

But let’s say they succeed, okay, let’s look at a map.

At the very northernmost part of the island is the capital, Taipei City, along with most of Taiwan’s industry. It would make sense for China to invade there, however, the Taiwanese military knows that, so most of their defence is in that area.

A similar dillema faced the The U.S. and Britain in 1944. They chose not to invade Pas de Calais because the Germans knew they had wanted to, and thus the Germans concentrated most of their military capital there. The allies opted to go for Normandy instead, which was lightly defended, and were able to secure it. In the end, they got Calais anyway.

Like Calais, a Chinese invasion of Taipei would most likely be repulsed. Because Taiwan has homefield advantage, it can easily resupply it’s defensive forces, whereas China has to ship them across the strait. Also, China would be fighting in an urban landscape, needlessly giving the defence another force multiplier. The majority of Taiwan’s Hsiung Feng II and III Anti-Ship Missiles, as well as it’s aircraft and (admittedly small) navy are also located in the north. Among CSIS’s war games, several teams tried to invade the north, and it was simply too difficult to get a beachhead and then hold on to it long enough for resupply. So for all these reasons and more, their most likely scenario was an invasion through the south.

But now we have a problem. Even if you grant that China is able to successfully secure a beachhead in the South, they know have to fight their way up the entire island.

Looking at the map again, you can see that most of Taiwan is mountaneous, however the coast is fairly flat. So with the sea to the west and the mountains to the east, the Chinese will be bottlenecked along the coast, fighting their way up north against concentrated Taiwanese forces. This is similar to the Allied invasion of Italy, which as you know failed due to it’s mountaneous terrain. This is a point for Taiwan, as although China outnumbers Taiwan, they can’t exploit this advantage by lengthening their offensive line and trying to encircle Taiwanese army groups.

So this natural chokepoint ends up stifling any Chinese invasion from quickly ending the war. Why is this important? Because as I said earlier, China has the naval advantage in the short term, but once the U.S., along with it’s allies (South Korea, Japan, Australia, Canada, The United Kingdom, and possibly Poland, Italy, or France) bring their forces to bear, Chinese naval superiority in the Taiwanese strait will be very difficult to maintain. The most probable outcome is a contested strait in the mid to long term. This will be the end for their invasion however, as resupplying of troops and equipment is now unthinkable without naval superiority. The losses to attrition would be to great. So now you have, say, 40,000 to 60,000 Chinese men, along with all their vehicles and military equipment, stranded along the chokepoint that is the western coast of Taiwan. Taiwanese forces are making their way from the north to the south, building up along the southern front. By now the international players mentioned above have entered the war, along with their navies and airforces, and to a lesser extent their armies.

So in the short to mid-term time scale, it looks pretty dire for China. But let’s move to the long term, because I sense that might be your objection to this argument. You could, for example, counter that this all might be true within the first 6 months, things may go badly for China. But because of their greater industrial capacity, they would eventually win the war. Noah Smith wrote in his blog post, Manufacturing is a war now, that China is much closer to a war time economy then western countries.

“The democratic countries have all struggled to respond to China’s industrial assault, because as capitalist countries, they naturally think about manufacturing mainly in terms of economic efficiency and profits unless a major war is actively in progress.

Democratic countries’ economies are mainly set up as free market economies with redistribution, because this is what maximizes living standards in peacetime. In a free market economy, if a foreign country wants to sell you cheap cars, you let them do it, and you allocate your own productive resources to something more profitable instead.”

But when a war comes, Noah is afraid that China will easily turn it’s auto industry into a tank making industry, and the U.S. and Germany and Japan will be flat footed. It’s tough because the U.S. is doing the right thing, it is increasing average welfare by not dabbling as much as China in it’s economy. But Noah is right that it comes with a tradeoff.

However, I don’t buy that just because China is in a war-time economy now, and the U.S. and it’s allies are not, that China will win the war in the long term. The U.S. government has less of a controlled economy because it has less of an incentive than China, but if China declares war on Taiwan, well now the incentive structure has changed, not just for the U.S., but for South Korea and Taiwan and Japan and Australia too. I put a reasonably high probability on things not staying equal come war time, so I don’t think it’s fair to predict off of current manufacturing statistics given the necessity of war has not yet arrived. And sure there is an advantage to already possessing the manufacturing capability of China in the short term, but what does that give China in the short term? As I’ve argued above, not very much. It is simply too tall a task for China to successfully invade Taiwan in a short enough time span before the U.S. and it’s allies properly react. In the mid-term, this means bringing the majority of their forces to bear, in the long term, this means centrally planning their economies like they did in World War 2. This will take years, however, the U.S. and their allies currently have the technological advantage and the defensive advantage.

And another thing. I wrote above that Germany failed in it’s attempt to evict the Soviet military. But I never said why. Lots of ink has been spilled over this, but I think most economists would subscribe to Phillips Payson O’Brien’s view, which was that Germany’s ability to manufacture tanks, planes, ships, and food, was effectively curtailed by the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

Jack Thorlin summarized this in his book review for ACX:

“In the European war, American and British airpower: (a) directly destroyed a significant amount of productive capacity, (b) rendered remaining capacity far less efficient, (c) made it impossible for the Germans to defeat western ground forces, and (d) compelled the Germans to waste tremendous resources on air defense and exorbitant, ultimately ineffective vengeance weapons.

In the Pacific, the United States used carrier-based airpower, submarines, and bomber-deployed mines to isolate Japan from the resources of the empire it conquered in 1941-42. American bombers also directly destroyed factories and transportation systems, leading to similar levels of economic dysfunction as in Germany.”

Germany and Japan were defeated because their ability to manufacture the tools of war was disabled by the Allies.

In what world is China going to be able to accomplish this? For China to effectively curtail the U.S.’s ability to manufacture the tools of war in the long term, it would have to be able to attack the continental United States. If you know anything about geography and military strategy, you will know this is basically impossible. This war will be fought and won in the straits of Taiwan. This means that the U.S. will be able to go into full war economy unmolested, indefinitely. So in the long term, I am very bullish on the U.S.’s ability to whip itself into shape. This doesn’t even get into China’s demographic challenges when it comes to sustaining a prolonged war effort.

To summarize: For China to successfully invade Taiwan, they would need to achieve complete naval and air superiority over the strait (hard) then successfully pull off probably the biggest and most logistically difficult troop maneuver in human history (very hard), then work up along the entire coastline before the U.S. and its allies cut off their supply lines (basically impossible). This is why, if you look at most wargames, the United States wins, albeit with heavy losses. There are scenarios where Taiwan is more easily captured, but there are also scenarios where something goes wrong in China’s series of events that lead to a victory. On average, they lose.

These arguments are not meant to give the impression that I think the U.S. is doing a great job, or that Taiwan has nothing to be worried about, again, it is merely meant to change your probabilities. Noah Smith is right in ringing the alarm bells. At a certain point, China will have the technological and the naval advantage if the U.S. and its allies are caught as do nothing to stop the bleeding. I would say that if things keep going how they are, China gearing up for war, The U.S. staying as apathetic as Gondor, your probability that the U.S. loses should update by about 3 or 4 percent less each year. Right now, if China invaded Taiwan today, I would put a 20% chance of them succeeding. If you asked me this question, I would probably reply with 70% if things keep going the way they are, 40% if the U.S. changes course. Obviously, we are dealing with a lot of variables and predictions at this point, so this conversation is less useful. The purpose of this essay is to argue that no, you should not be that worried about China successfully invading Taiwan in the next, say 3 or 5 years, the odds aren’t too bad from a military strategy perspective.

However, those odds have been decreasing since 2000, and will continue to decrease if the U.S. and its allies don’t start listening more to Noah Smith. Noah and I are both die-hard optimists, and even I can’t help but give a bittersweet take on this issue. If you weren’t worried about the U.S.’s unpreparedness, you better be now!

"...it would have to be able to attack the continental United States. If you know anything about geography and military strategy, you will know this is basically impossible."

I somewhat disagree as China will launch a massive cyber warfare attack hoping to cripple America's infrastructure, which is why hardening IT infrastructure is critical, but it is relatively easy and inexpensive to accomplish.

I think we need to look at scenarios in the gray zone around what constitutes a blockade of Taiwan by the PRC.

It's easier for the PRC to deploy ships around Taiwan then it is for the US to counter, and the logistics are all in the PRC's favor. Thus their optimal strategy would be to exhaust the US ability to replenish naval forces around Taiwan in a way that doesn't commit them to an invasion.

The right strategy is not to fight the United States for control of the waters around Taiwan, it's to wear the American people down to the point that they see sending ships to defend a Taiwan that isn't being attacked as boring and costly. Once the will of the American people is broken, in the way that it was in Afghanistan in a different kind of forever war, the United States will withdraw and the PRC can move in at their leisure.

The PRC also has the ability to make military and coercive economic moves to unsettle potential Taiwan allies in the region and to crash the Taiwan economy. Again, these don't need to take the country to the brink of war, they only need to be bad enough to create a failed economy and disinvestment. If the people of Taiwan are forced to live for a few years in economic misery then the invasion calculus may get easier as more Taiwanese become apathetic or the PRC creates a fifth column movement.

What vitiates against all this is that a logical strategy for the PRC to reclaim Taiwan does not intersect at all with Xi's personal agenda or actuarial timetable. It's highly likely that if Xi it's going to pull the trigger then he'll choose a manufactured crisis and an accelerated timeline.